The Western Australian state budget has revealed that the conservative Barnett government has not spent any of the 150 million Australian dollars allocated for its reform of Western Australia’s remote Aboriginal communities. Potential health service costs could be enormous when it is taken into account that a weakening of cultural practice is likely to produce similar symptoms to post traumatic stress disorder. There is certainly a negative correlation between loss of culture and poor health. A weakening of cultural practice is likely to produce similar symptoms to those experienced by sufferers of Post-Traumatic Stress Syndrome. Those suffering from cultural loss are disproportionately represented in prisons, infant mortality, suicide, drug dependence and substance abuse and general medical conditions, as well as lower life expectancies.

Threats to close remote Aboriginal communities

The Western Australian government has announced that it will close between 100 and 150 remote indigenous communities.

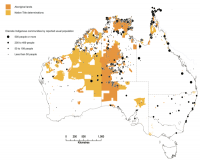

1,300 people live on the smallest 174 Aboriginal communities, this is considered by the state government to be unviable.

Specific communities that will be closed have not been named, making it difficult to predict exact cost benefits of closures.

A document prepared by the federal government in 2010, titled “Priority Investment Communities – WA”, categorised 192 of 287 remote settlements as unsustainable

Low employment and economic viability of the upkeep of such communities is the predominant argument for the closures although social dysfunction and poor health in such communities are also cited as reasons for their closure.

Premier Colin Barnett has stated that such communities do not provide opportunities for employment or education of their residents.

The state budget has revealed that the Barnett government has not spent any of the $150 million allocated for its reform of remote Aboriginal communities.

The sum, sourced from WA Nationals’ multi-billion-dollar Royalties for Regions scheme over three years, was earmarked to implement changes in regional communities, which could mean the closure of remote Aboriginal outposts and the removal of people to larger, better-resourced towns.

Barnett set the reform process in train in November 2014 after asserting that between 100 and 150 of the state’s 274 remote communities were unviable and would need to close.

The government’s plans triggered angry protests around Australia last year, including a mass rally that shut down the streets of Melbourne’s CBD.

But this year’s budget papers show that none of the $150m in a special purpose account has been spent, despite the appointment mid-last year of former WA housing chief Grahame Searle to lead a reform unit to examine the criteria for a sustainable remote community, which are likely to say that children must go to school and live in a safe environment.

Opposition Aboriginal affairs spokesman Ben Wyatt said the lack of action prolonged uncertainty and frustration for Aboriginal people. “The government is still trying to dig its way out of Mr Barnett’s decision to close 150 communities. And clearly they’re still trying to come up with a coherent plan,’’ he said.

Government figures show about 12,000 indigenous people live in more than 270 communities, and about 115 of those communities have an average of four people living in them.

Mr Barnett argued the shrinking of communities was necessary for the safety and education of some indigenous children, but also because the federal government was progressively “vacating the territory” in providing essential electricity and water services to two-thirds of WA’s remote communities.

Regional Development Minister and Nationals leader Terry Redman has indicated that spending of the $150m would begin after an intense consultation period.

He said in the past 12 months the responsible ministers, Mr Searle and the reform unit had consulted with leaders in remote communities and towns throughout the Pilbara and Kimberley.

“In all the discussions that have taken place about reform, we have found no one who is prepared to defend the status quo,” he said.

Robin Chapple update UPDATE: Tuesday, 10 May 2016

Prevention of forced closures of remote Aboriginal communities bill 2016

I tabled a draft version of this bill I have been working on for the past six months on Tuesday, 10 May 2016. In tabling a draft, and subsequently releasing a copy for public comment, I want to ensure that Aboriginal people are given an opportunity to contribute to the wording, scope and intention of this important piece of legislation.

The purpose of the Prevention of Forced Closure of Remote Aboriginal Communities Bill 2016 is to prevent the forced closure of remote Aboriginal communities. It acknowledges that Aboriginal people in Western Australia are the traditional owners of the lands in the State, and have a living cultural, spiritual, familial, and social relationship with these lands. Furthermore, it seeks to hold Western Australia accountable for its agreement to take responsibility from the Commonwealth of Australia for providing municipal and essential services to support remote Aboriginal communities

Remote Aboriginal communities are communities wholly or principally composed of persons of Aboriginal descent as defined by the Aboriginal Affairs Planning Authority Act 1972 section 4, and are listed in the Government document entitled “Priority Investment Communities – WA”. Some of these communities may be renamed or known by a different name.

Forced closure refers to any action taken without the free, prior and informed consent of residents that has the aim or effect of closing the community or relocating residents. It also refers to deterring people from living in the community through inadequate municipal or essential services. Municipal and essential services include power, water, sewerage, infrastructure, education, health services, and waste disposal.

The Bill would require decision makers to adhere to the principles of the Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples, especially Articles 8, 9, and 10 which outline the right to belong to an indigenous community and to not be removed from lands; Articles 3, 4, 18, and 23 which outline the right to self-determination and self-government in matters relating to their own affairs and development; and Articles 19 and 39 which outline the right to develop their own health, social, and economic programs and to receive co-operation and support from the State.

Should a public authority make a decision that leads to the forced closure of a remote Aboriginal community, which includes the inadequate provision of municipal or essential services, the Bill would enable residents to apply to the State Administrative Tribunal for a review of a decision to close their community. Residents must apply within six months after the decision was made; or if the community was unaware of the decision, six months after they became aware of it. Applications for review must be made in writing, or if made orally, put into writing by the executive officer as defined in the State Administrative Tribunal Act 2004 section 3 (1).

Key considerations

Economic

Indigenous economic development in small remote communities can be achieved with the right conceptualisation. Elements of remote indigenous life can be recognised as assets and resources of a three sector economy incorporating a customary sector made up of aboriginal cultural activities and structures as an asset and resource alongside the public and market sector. This would greatly help sustainable livelihoods for the residents of small remote indigenous communities.

Traditional indigenous activity has value environmentally and economically but is often unrecognised because it is seen as “informal” or not explicitly economic. This is because false distinctions are made between formal and informal natural resource management activities, the latter often being unrecognised and usually unremunerated.

Aboriginal leaders have shown to care about their people having “real” jobs (jobs in non-traditional sectors). Their only preference being that such jobs are situated on their traditional lands.

In addition to improved health services, Aboriginal Community Controlled health services, defined as those in a local aboriginal community, also deliver far greater value for money in regards to health than mainstream services.

Activities such as land care serve two purposes of cultural development, health and management of land that would otherwise need to be provided by government separately can save government costs and contribute to the “viability” of such remote settlements.

There is evidence that moving indigenous people of country and away from meaningful cultural activity will actually increase welfare dependency:

The perceived advantages of servicing centralised populations have been considered by funding agencies to outweigh the deleterious social consequences of artificially forcing different indigenous cultural groups to live together. Centralisation has often resulted in social dysfunction, weakening of traditional governance structures and increased welfare dependency.

Social

The knowledge and skills of indigenous people on country is only applicable to their traditional country and needs to be practiced regularly to be of use. It is important to note that Indigenous ecological knowledge (IEK) is often rooted in indigenous languages and cultures and is often regionally specific. The primary vehicle for the intergenerational transfer of this valuable knowledge is through practice. Practice is enormously difficult or impossible, however when indigenous peoples are unable to live on their country.

Migration by indigenous peoples would cause significant problems for the communities which they migrate to. Some suggest that the free market can succeed in remote and very remote Australia. Others suggest that in the absence of mainstream commercial opportunity at remote indigenous communities, it is imperative to move the people to the opportunities. The latter approach is naïve at best, because it ignores people’s agency and their active links to the ancestral lands that they now own. Also given indigenous people’s low educational and health status and their economic marginality, labour migration could be disastrous for migrants, as well as for communities where they move.

For governments to persist in their pursuit of indigenous employment separate from cultural considerations would be futile due to the strong cultural links that Aboriginal people hold, including connection to their traditional land.

Potential health service costs could be enormous when it is taken into account that a weakening of cultural practice is likely to produce similar symptoms to post traumatic stress disorder. There is certainly a negative correlation between loss of culture and poor health. A weakening of cultural practice is likely to produce similar symptoms to those experienced by sufferers of Post-Traumatic Stress Syndrome. Those suffering from cultural loss are disproportionately represented in prisons, infant mortality, suicide, drug dependence and substance abuse and general medical conditions, as well as lower life expectancies.

Unless it is recognised that indigenous culture is inseparable from indigenous economic development as both an asset and resource for enterprise, labour and importantly land, efforts to increase indigenous employment will be futile.

There could be substantial savings to the expensive justice and juvenile offender rehabilitation system from on country activities. For example, Learning language, bush knowledge and visiting the country of ancestors assists in the campaign to minimise young people’s involvement in the justice system. Indeed, some, including those deeply involved in the court system, claim that ‘culture’ is more capable in this regard than many other diversionary and sentencing options.

Examples of successful remote indigenous initiatives

The Yiriman Project

Supported by the Kimberly Aboriginal Law and Cultural Centre, Yiriman’s work mostly involved hosting what local people call “back-to-country” trips. This involved removing troubled youth for periods of time, hunting and collecting food, meeting others, going on country with their elders, taking care of country and walking as a means of learning stories, becoming healthy, building their skills and respecting the old people.

In so doing, the organization brought together the young, elders, other community members and a range of other people, such as land care workers, educationalists, health practitioners, researchers and government officials, but it also led to a range of other events including people’s involvement in: landcare; cultural education; fire management; science and economic development; health care; and education tourism training for employment language regeneration. Several employable skills were learned by young people on such trips.

Bush light program

This project supported off grid solar battery energy for remote indigenous communities, and local contribution to operation and maintenance, including contribution from rent. This was self-sustaining during the solar battery life of 10 years. Such projects could significantly reduce the cost of external power supply to remote indigenous communities.

Systems are built specifically for remote areas with extremes in temperature and other conditions. They are very reliable and provide residents with a ‘daily energy budget’ designed to meet their day to day power needs.

Self-build projects

Self-build projects in small remote indigenous communities including WA, have been shown to be cost effective in providing adequate housing sensitive to the needs of its occupants with shared planning and construction. Support of such services could greatly reduce the cost of government housing provision. The attributes shown in the self-build project offer a counter narrative to the narrative of indigenous passive dependency and lack of initiative/opportunity often heard in the mainstream media from conservative politicians and cited as reasons for closure of remote communities. This is also a counter point to the apparent lack of training opportunities for indigenous people in remote communities.

Half of the participants in the study’s self-build projects did so to be able to get away from negative influences of larger regional centres. This desire of people who live in remote communities could be used to help build houses, skills and networks in indigenous remote Australia, contributing to their sustainable livelihoods.

Defending remote communities

In order for an economic argument to be made for allowing remote aboriginal communities to stay open, Aboriginal activities on country must be shown as an asset to government and the wider economy. This is a topic given little attention in the mainstream media and would be a positive move beyond seeing Aboriginal people only as economic liabilities with only their human rights as reasons to maintain their communities.

There are significant economic development options by Aboriginal people remaining on traditional country, including employment and training which often lead to job opportunities. Many of the programs offering this would not be effective without indigenous people’s connection to country. There would also be economic benefits, such as carbon abatement, land care and making of cultural artefacts that could not continue in larger town centres.

For indigenous economic opportunity to be recognised, the identity of Aboriginal people as being inseparable from country must be worked with rather than fought.

Population figures

For figures on the populations of WA Remote Communities click here .