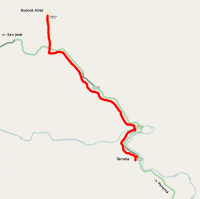

On Tuesday, October 6th, two years after the fraud that approved the Free Trade Agreement with the U.S., a Popular March for Dignity in the Southern Region of Costa Rica was held. More than 150 activists marched from the entrance of the Indigenous Territory of Térraba, towards the center of the county of Buenos Aires. One step after another, they covered a total of 13 kilometersl. Different communities from all over the South face struggles against the expansion of pineapple plantations, the building of Diquís Hydroelectric Project, plans of an international airport to be built on the land of “Finca 9”, and plans to develop marinas and industrial tuna farms in Golfo Dulce. Besides all these foci of resistence, there is also a struggle in favor of the Indigenous Autonomy Bill.

The southern region is one of the poorest in Costa Rica. Since the 1930´s the United Fruit Company moved its banana plantations from the Caribbean coast to the southern costarrican Pacific coastline. Since then monoculture and cattle have dominated the landscape of this part of the country.

At 8 am everyone gathered at the entrance of the Indigenous Territory of Térraba to begin the march up the Interamerican Highway, one of the main transit routes and means for commodity circulation of the region. Once the Highway was taken, occupying both lanes, the March began its slow and ardent advance that would arrive at the front of the municipality of Buenos Aires, 13 kilometers away. At 8:30 a.m. 100 activists embodied the “Popular March for Dignity in the South”. In the beginning, Police arrived with few cops on motorbikes and in small squad cars. The actions of the police were limited to regulating transit and they hardly intervened with the on-going March.

Making itty bitty stops along the way, the protesters on their way to Buenos Aires handed out flyers to the passing cars and to the locals who live by the Highway. Along the march, more people joined and the group went up to 150 activists. Some of them started walking from their communities as early as 2 a.m. to take part in the March. Others came the night before after traveling from the capital and other parts of the Central Valley to show solidarity with the groups in struggle in the South.

At 9:10 a.m. the protest reached the bridge over Río Térraba. They had reached the end of Indigenous Territory At this point the activists took up only one lane to give chance to buses, ambulances and any individuals transiting down the Highway to pass. They wanted to guarantee their right to protest without generating negative responses from the population.

Amongst those who participated in the Popular March, were kids of a only several months of age carried in their mother’s arms, youth in various forms, shapes and sizes, peasant women whom are heads of their households, students and even a 90 year old indigenous peasant from Térraba. Despite the tremendous heat that tortured and left the participant’s skin burnt, the march kept going and reached the town of El Brujo. When the sun had reached its cruelest point, at about 11:30, the protesters decided to hop onto the cars they had and onto the bus that had brought the activists from the Central Valley. That’s how they covered the last 5 Km to the entrance of Buenos Aires. They avoided the heat to finish the march with strength, coming into the center of the county.

At noon, the march arrived at the entrance of Buenos Aires. From there the protesters went to the premises of the Instituto Costarricense de Electricidad (ICE) to show their firmness against Diquís Hidroelectric Project.

As the march went on, by-standers that saw the column of protesters pass by with pro-Autonomy flags and chants against the expansion of pineapple plantations, stood glaring as passive observers, or in other cases showed some degree of sympathy by taking a flyer through the window as they drove by, or even honking as a simple gesture of support.

At 1 p.m. the protest gathered in front of the municipality of Buenos Aires. The local government’s president Juan Bautista Blanco, of Partido Acción Ciudadana (PAC), lives in indigenous territory but is not indigenous, had sent a letter to congress a few months ago on behalf of the local government, demanding that the “Bill of Autonomous Development of the Indigenous People” be rejected.

In front of the municipality, an “ICE employee” and self-acclaimed “reporter” tried to record the participants of the march with a video camera. This caused a minor confrontation. He appeared to be a tough guy, stocky and with a shaved head stating ironic and provocative arguments to defend his actions. According to his own perceptions, he was “just doing his job” as he directed the lens of his camera to the faces of protesters. He had to be protected by the police so that the protesters wouldn’t attack him. After a brief brawl, and a fired up dialogue, the police that surrounded the park (about 12 or more policemen and women) protected Oscar Ruin Cruz, who was identified by some protesters as part of Channel 6 and as a reporter who used to work for “Al Día”, a newspaper of “Grupo Nación” (the major newspaper of the elite in the country). This agent had credentials that identified him as an ICE employee, specifically for the Diquís Hidroelectical Project. Towards the end of the protest in front of the municipality, several activists unloaded some strong and clear words aimed at the representatives of ICE who were recording the protest.

An indigenous peasant and activist, who had been incarcerated years back for his struggle against the illegal logging of forests in the South, addressed the protesters, recalling the abandonment, manipulation and neglect of the State that the indigenous communities have endured.

Throughout the cars with official ICE logos on their side passed the march. This caused reactions from activists. There was booing, whistling and chants: “Rivers for life, not for death!”. And a huge truck went by thundering and carrying ICE’s heavy machinery. But there´s a paradox to this. Roughly 10 years ago a wide segment of Costarrican society defended ICE in the streets against the attempts to privatize the company, like in the “Combo del ICE” in 2000. But for the indigenous people in the South, the ICE and their dam have a bitter taste.

After the rally in front of the municipality ended, at about 2:00 p.m., the protesters gathered at a big church room to eat and reflect about the day. There was also some space to discuss future strategies in their struggles. At 3:30 everyone started going back to their communities.

No to the expansion of Pineapple monoculture!

No to the expansion of Pineapple monoculture!

Today, banana plantations have been replaced by massive pineapple and African palm monoculture. Bio-fuel is produced out of palm oil and these pineapples are exported in great majority to the U.S. and Europe.

This region has had a series of social and environmental conflicts due to the impacts of the pineapple agri-industrial business. Communities located near the plantations have suffered drastic changes in the local economies in addition to severe negative consequences due to the destruction of natural resources.

The pineapple business extracts huge amounts of water for irrigation from the rivers of the county of Buenos Aires. This water is then lacking further down the river where there are communities that need it. The water left for the local residents is polluted with agrochemicals. Workers of the pineapple fields are directly exposed to these chemicals that destroy their health. Activists of social movements and organizations that strongly denounce these situations have received death threats.

For more info:Frente de afectados por la expansión Piñera

African Palm monoculture isn’t as extended as the pineapple plantations, but there are groups in Costa Rica that are trying to give the business a push stating that there’s a need for energetic sovereignty. Like in other parts of the world, the demand of bio-fuels is on a rise as a consequence of the high prices of oil and the foreseeable oil peak.

Bread today - hunger tomorrow!

Bread today - hunger tomorrow!

“Energetic sovereignty” is also a discourse used by the white collar technocrat bosses of Instituto Costarricense de Electricidad. ICE has been trying to dam Rio Térraba since 1964 against the will of the people.

The fact that ICE is a public company, which implies that costarrican civil society owns it, makes the conflict between the firm and the inhabitants of the region more paradoxical. “Boruca Hidroelectric Project” was stopped several years back due to the resistance of the indigenous people that would have been affected by the dam.

The idea of building a dam in the South unfortunately didn’t fade away with the fall of Boruca H.P. Instead, the ICE has modified its plans and is now on its way to try to re-launch Diquis H.P. This project would be less monstrous than its predecessor, but would still be the biggest dam in all of Central America, with a 631 MW capacity. Like in other parts of the world, politicians and technocrats try to “persuade” people by posing the threat of fearful hypothetical scenarios. This technique is applied in Costa Rica in the case of the dam, but also in other notorious ones. Costa Rica exports electrical energy but the lobbyists of the electrical company threaten with the possibility of shortages and black outs, then declaring Diquis H.P. of “national interest".

The dam would cause severe environmental changes and would flood more than 200 archeological sites and 800 acres of ancient indigenous territory. It would also force 1100 inhabitants to abandon their homes and be “relocated” somewhere else.

But the struggle against large scale dams can be won as the case of "La Parota" shows in the State of Guerrero, Mexico. A decentralized system with many small hydroelectric dams, like “El Encanto Hydroelectric Plant”, could produce enough energy to supply to communities without forcing people out of their land or flooding archeological sites.

Land conflict: this is the situation of the community of Finca 9, in Palmar Sur.

Government and Capital of the tourist industry want to build an international airport to increase

the wonders of tourism and suck the wealth out of nature, its resources and landscapes such as

in Bahía Drake and Corcovado National Park. This community of about 40 families has lived off the

land producing beans, maize, yucca, plantain, and other products. They live in 240 acres that had

been previously exploited by the banana companies, before Corbana vanished 9 years ago without

paying the salaries and benefits that they owned their workers by law. The peasants of Finca 9

were then grouped in a government controlled cooperative, INFOCOOP. The community itself is

organized though. The Rural Women’s Network and the Group in Defense of the Land of Finca 9 are fighting together against the representatives and administrators of

the cooperative that have links to the local government and use the community’s resources in

their favor. According to the testimony of a young peasant woman from Finca 9, those who came to

the Popular March did so after being threatened by the pro-airport “co-op leaders”. Part of the

community didn’t show up fearing that they would be kicked out of the cooperative thus loosing

their land. The struggle in Finca 9 continues currently, and for the next day after the Popular

March for Dignity, there were more actions already planned to let their cry be heard and have the

community remain on their land.

Finca 9 has somewhat a parallel to San Salvador Atenco, Mexico.

(Video 1, Video 2, Timeline, article) Vicente Fox’s government attempted to

expropriate the peasants of this community, indigenous in its majority, to build the greatest

meanest shiniest airport ever that would give the government and its president’s image great

appeal.

For 15 years now, the members of the indigenous communities of Costa Rica have been fighting for the "Bill of Autonomous Development of the Indigenous People" (file 14.352) ) that, in theory, would protect their rights as an ancient and historically deep community.

Members of the National Commission of Indigenous Matters deny the importance of this bill. Such institution, presided by Genaro Gutierrez, a local “leader” from Térraba who is close to the party in office Partido Liberación Nacional, takes advantage of the current state of the indigenous question, as it manages the resources that the central government allocates, and clears the way to the usurpations and transactions that guarantee his permanence in positions of local power. According to the testimonies of several members of the community of Terraba, where Gutierrez is also president of the Association for Indigenous Development, he has taken charge of hindering the Autonomist Movement’s positions, guaranteeing that those who do not follow government’s policies are excluded of any participation. If you don’t follow governmental policies, then “you’re out”. “You’re out” if you defend Autonomy or denounce corruption, say local indigenous women. In fact, Gutierrez is seen as someone who disowns and denies the cultural heritage of his own people of Térraba.

The Autonomy Bill would also in theory protect their ancient traditional knowledge and would prevent the dispossession of this knowledge by transnationals in the context of the Free Trade Agreement, an issue that has been exposed before National Congress.

The threats posed over Golfo Dulce

The threats posed over Golfo Dulce

Besides all these huge issues, there’s also the plan to install “Tuna Farms” in Golfo Dulce. Apart from the inexistent environmental studies on the impact that this could bring for the gulf, one can foresee problems similar to those of the salmon farms in Chile. There, fish are treated with antibiotics and pesticides that cause permanent water contamination and may result in strengthened antibiotic resistant bacteria. The fact that fish are reproduced in limited spaces, in which large amounts of fish are overcrowded for an intense industrial exploitation, makes the medical treatment necessary to cure mass illnesses ineffective sometimes. Also, it is probable that the patterns of exploitative use of work force that are seen in Chile aret repeated in Costa Rica. There are many doubts regarding fish farms.

Like in many parts of the country, private ventures are also planning the construction of a marina in Golfo Dulce. Last year the project to build a marina in Puerto Viejo fell apart and the "Crocodile Bay Marina" had also been haulted. The Supreme Court took in an appeal against the marina presented by the community of Puerto Jimenez. While Government tries to pass a bill that simplifies the proceedings for the installation of marinas, other congressmen and congresswomen question the legality of this law that favors foreigners who own yachts.

The building of the marina would actually generate few jobs, but would cause great environmental damage. After the construction, the few jobs that are left are taken by foreign personnel and the community would not benefit from the infrastructure. On the contrary, the access to beaches becomes practically private. According to their plans, Crocodile Bay Marina would hold space for more than 250 yachts. These yachts would pollute the surrounding water with the oil and fuel from their engines.

More info:

- Voces Nuestras Interview - (Nr. 10. at the bottom)

Note:

The faces of those who took part in the March for Dignity in the South have been distorted to protect their identities: Counter-power is made by all of us and by no-one..

colectivo pequeñas hermanas:

We are a collective of militant anticapitalists, that are involved in the struggle to subvert the imposed order vindicating art as a political weapon. This is a project of audio-visual counter-information, a loudspeaker for the protagonists of the disobedience of the people.