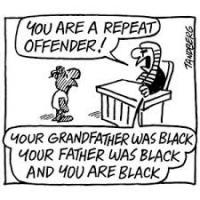

Australian indigenous communities are taking new, innovative approaches to keep children out of detention - but their success hinges on Australian government support, to reverse Australia’s crisis of indigenous youth incarceration, said Amnesty International Secretary General Salil Shetty, launching a national report. Shetty is in Australia to call on the government to support indigenous-led justice reinvestment programmes, in response to the soaring overrepresentation of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children in detention, who are incarcerated at 24 times the rate of non-indigenous children. Australia locks up indigenous children, from as young as 10 years old, at one of the highest rates in the world.

Overrepresentation is rising, with indigenous children making up less than 6% of the population of 10–17 year-olds yet more than half (58 per cent) of young people in detention.

“Australia has a long and tragic history of removing indigenous children from their families and communities. We will see another generation lost to failed government policies, unless Australia shows the vision to support and fund indigenous people to be the architects of the solution.”

“I’m inspired by the innovative work indigenous communities are doing across Australia to bring up a new generation of young people, but the Australian government needs to catch up, and fund the programmes that have been shown to work in keeping indigenous kids out of prison, and making communities safer - it’s a win/win for all Australians,” said Shetty. Shetty has described Australia’s punitive approach as “staggering” and “an embarrassment for Australia”.

“In other countries I have visited recently, such as The Netherlands and Mexico, children under 12 are not held criminally responsible. Yet, Australian law holds children criminally responsible from the age of just 10, which is out of line with international standards.”

The report, ‘A brighter tomorrow: Keeping indigenous kids in the community and out of detention in Australia’, highlights that Australia is detaining Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children at the highest rate since the Royal Commission into Aboriginal Deaths in Custody 20 years ago.

It lists 16 recommendations for action that the Australian government can take to comply with international human rights obligations, such as ending mandatory sentencing of young people, which only contributes to increasing detention without reducing youth crime. “Australia needs to make communities safer - but locking up children has been shown not to be the answer,” said Shetty. “Australia must seize this once-in-a-generation chance to keep Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children out of prison and make communities safer.”

Shetty saw first-hand the promise of a new approach on his visit to the NSW town of Bourke, where community leaders are pioneering the Aboriginal owned and run Maranguka initiative. They have partnered with non-profit group Just Reinvest NSW to implement the first trial of justice reinvestment in Australia, to reduce youth incarceration rates and make Bourke a safer place to live.

Justice reinvestment works by shifting investment in prisons to investment in communities. The approach increases community safety by addressing why crimes occur in the first place, identifying circuit breakers, building alternative pathways in partnership with community and local agencies, and thereby improving outcomes for low-income children and families.

In Texas, from 2007 to 2012, the approach led to 2,800 fewer young people behind bars, allowing Texas to close eight juvenile correctional facilities. Meanwhile, the state’s crime rate dropped to the lowest it had been since 1974.

The Maranguka–Just Reinvest NSW project is one of the first in the world to trailblaze an indigenous-led approach to justice reinvestment.

Their model has brought together NSW Police, the Australian Bureau of Statistics, NSW Bureau of Crime Statistics and Research, government agencies such as Department of Premier and Cabinet, health, housing, education, employment, Family and Community Services, Aboriginal affairs, philanthropic and community organisations.

Government must support community programmes

Amnesty International is calling on Australian governments to commit long-term funding to ensure the success of the Maranguka-Justice Reinvestment project, and many other community-led programmes around the country. As the US has found, it is far cheaper to invest in communities rather than prisons.

In Australia it costs $440,000 per year to detain each child, meaning the cost of just one year of detention could instead put a young indigenous person through an entire undergraduate medical degree.

Australia has been condemned by the United Nations for breaching its international obligations around the incarceration of indigenous young peoples, such as for failing to detain children only as a last resort. [Prime Minister Tony Abbott said famously in March 2015: "I really think Australians are sick of being lectured to by the United Nations." He was responding to a report by the UN special rapporteur on torture, Juan Mendez, which found multiple cases of Australia breaching the international convention against torture in regard to refugees.]

Worst in Western Australia

The Amnesty International report finds Western Australia incarcerating indigenous young people at the highest rates in Australia - and those rates are rising. The report ‘There is always a brighter future: Keeping indigenous kids in the community and out of detention in Western Australia’, was three years in the making, and includes research in Albany, Bunbury, Perth, Kalgoorlie, Geraldton, Broome, Mowanjum, Fitzroy Crossing, Halls Creek and Kununurra. It finds indigenous young people in Western Australia are an astonishing 52 times more likely to be in detention than their non-indigenous peers. This is more than twice the national rate of overrepresentation in Australia. Nationally, indigenous young people are 24 times more likely to be in detention than non-indigenous young people.

“The overrepresentation of indigenous children in detention around Australia is already a national crisis - it’s shameful that this is twice as bad here in Western Australia,” said Claire Mallinson, National Director of Amnesty International Australia.

Indigenous young people make up just over six per cent of 10–17 year-olds in Western Australia, but they make up more than three quarters, or 79 per cent, of the young people in detention. Furthermore, the overrepresentation of indigenous young people in detention in Western Australia is increasing and is the highest it has been in five years.

Another lost generation

“Western Australia has a long and tragic history of removing Aboriginal children from their families and communities, a history that is sadly repeating. We will see another generation lost to failed government policies unless this government gets smarter about this, and fast,” said Mallinson. “We all want to make Western Australia communities safer. We all want to keep children safe. Locking them up has been shown not to be the solution and must truly be a last resort.”

The report finds the reasons for the staggering rates of Western Australia Aboriginal youth detention include a failure to adequately support Aboriginal community led programmes at the early stages of contact with the justice system; police discrepancies in giving cautions; strict monitoring and enforcement of bail conditions; mandatory sentencing; and inadequate diagnosis and support for those who have Foetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorders. Underlying these may be issues of homelessness and overcrowding, family insecurity, poverty, cultural disconnection and substance misuse.

Amnesty International’s research found Western Australia police, when coming into contact with children committing an alleged offence, were much more likely to arrest Aboriginal children than non-Aboriginal children. Police arrest Aboriginal young people two thirds, or 66 per cent, of the time, whereas they arrest non-Aboriginal young people closer to one third, or 41 per cent, of the time.

End mandatory sentencing

The report also recommends the end of mandatory sentencing of young people, which only contributes to increasing detention without reducing youth crime. Western Australia is the only jurisdiction in the country where mandatory minimum sentences apply to children, contrary to international law. Amnesty is calling for the Home Burglary Bill currently before the Western Australia Legislative Council, the state’s upper house, to be amended so as not to include children. The Bill would expand Western Australia’s mandatory sentencing regime so that even more 16 and 17 year olds are caught in its net. It would result in more young people missing the last chance for rehabilitation before they transition to adult corrections, and there is no evidence it will reduce home burglaries.

Aboriginal-led solutions must be supported

The report has a strong focus on solutions. It finds a number of Aboriginal-led programmes around Western Australia, such as the Yiriman Project in the Kimberley and Nowanup in Albany, have shown great promise in supporting and rehabilitating Aboriginal children. Amnesty International urges the Western Australia government to support and fund these Aboriginal-led approaches, to address the root causes of crime at the earliest possible stage. The organisation also recommends Western Australia adopt the Justice Reinvestment approach, investing spending in communities instead of prisons. Justice Reinvestment has proved very successful in the US for keeping people out of prison while making communities safer.

“Western Australia spent over $36 million on locking up Aboriginal children last financial year - and this would skyrocket under the proposed changes to mandatory sentencing. Western Australia needs to reinvest that money in supporting Aboriginal families, and preventing crime in the first place. Community safety would be far improved, and children could remain with their families and communities where they belong,” said Mallinson.

The report is based on research carried out between mid-2013 and early 2015, and is informed by conversations and interviews with Aboriginal people, including representatives of Aboriginal organisations working with young people; court officers and lawyers of the Aboriginal Legal Service of Western Australia (The ALSWA) and other Aboriginal organisations throughout Western Australia.

The report shows that kids have healthy, happy childhoods when they live in loving and nurturing communities. It is kids’ connections with family and community that allow them to flourish, and sets them up for a good life.

But government policies are separating Aboriginal kids from their communities. By locking up kids as young as 10, past mistakes are being repeated and threatening Australia’s future as a fair, just and harmonious community.

Unless the high rate of Aboriginal youth detention is urgently addressed, an increasing number of Aboriginal young people will move into the adult justice system.

What can Western Australia do better? Amnesty International’s report details 16 recommendations for the Western Australian government.

Currently Western Australia is inadequately investing in and referring young Aboriginal people to programmes that address the underlying causes of offending behaviour before it becomes an entrenched criminal justice issue. It needs to increase state funding and support to the many successful Aboriginal-led initiatives that keep young people in communities and out of detention.

Western Australia also needs to work towards complying with international legal obligations, including the Convention on the Rights of the Child.

Some of the most pertinent the Western Australian government must address:

Scrap mandatory sentencing for kids

Western Australia is the only state or territory in Australia where mandatory minimum sentences of detention apply to young people. Mandatory minimum sentences prevent magistrates from considering all the relevant circumstances and are contrary to the international legal obligation that, for children, detention should be a last resort and for the shortest appropriate period of time. Despite mandatory sentences being contrary to international law, the Western Australian government was expanding the mandatory minimum sentencing regime for home burglaries at the time of writing.

Age of criminal responsibility too low

In Western Australia, children are held criminally responsible from just 10 years of age. Internationally, it’s accepted that 12 is the lowest minimum age of criminal responsibility. Based on available data, Aboriginal young people are impacted most by this low age of criminal responsibility.

Inadequate bail options

A lack of adequately supported bail accommodation contributes to the high rates of Aboriginal young people held in police custody and in detention without sentence. Over half of all young people in detention are unsentenced and 70 per cent of them are Aboriginal.

Police curfews – disruptive and problematic

Amnesty International consistently heard of police shining a torch through the front window of young peoples’ homes up to four times a night, including in the early hours of the morning, and requiring young people to present at the front door on demand. The way curfews are applied and monitored is disruptive of whole families and may escalate early contact with the justice system and deteriorate relationships between the community and police. While curfews may be appropriate in certain circumstances, the Western Australian government needs to transparently investigate the current approach to curfews.

Not enough options available to courts

When a young person is charged, Western Australia is failing to provide Aboriginal young people with appropriate diversionary programmes as an alternative to a court hearing. There is also a lack of adequate community-based sentencing options, particularly in regional and remote areas.

Failure to caution

Once Aboriginal young people come into contact with the police, they are more likely to be charged rather than cautioned when compared to non-Aboriginal young people. Under the Convention on the Rights of the Child, arrest should be a last resort. Failure to caution is a missed opportunity for referral to services to address the causes of offending. Young people cautioned at the beginning of their contact with the justice system generally do not go on to have further contact.

Better data for better solutions

Western Australia is failing to collect, make available and make use of information that would help to identify how and why the existing approach to youth justice is failing Aboriginal young people.

The Western Australian government told Amnesty International that problems with data are currently affecting its own capacity to plan for programmes.

Update: WA responds to report

Less than 24 hours after the Amnesty International report was released, Western Australia's Department of Corrective Services publicly responded, saying that "Commissioner James McMahon welcomed scrutiny from an Amnesty report which highlights the need for significant changes in the way service providers and the Department addressed the complex issues surrounding offending behaviour and Aboriginal people." The same day, the Department published up-to-date data on youth incarceration rates on their website -- one of the key recommendations of the Amnesty report. The Department commented that "having reliable, up-to-date statistical data on young people was integral to reducing reoffending".

“This is a welcome step from the Western Australia government. Amnesty International will continue to campaign for all the report recommendations to be implemented.”

For a full list of research, references and recommendations to the Western Australian government, please download "There is always a brighter future" (Western Australia full report) or see the national report on indigenous youth, A brighter tomorrow (National full report).

The Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander population has more people in younger age brackets than the non-indigenous population. In light of this, the National Congress of Australia’s First Peoples noted in 2013 that “unless the rate of increase in youth detention can be reduced, rates of incarceration across the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander population are likely to continue to increase into the future.”

The rates of indigenous and non-indigenous youth detention vary from one jurisdiction to another. Western Australia, Queensland and the Northern Territory have, respectively, the highest rate of over-representation of indigenous youth in detention; the fastest growing rate of indigenous youth detention; and the highest proportion of youth in detention who are indigenous. However, change is needed throughout Australia, and most recommendations apply to all Australian states and territories.

In Australia, each state and territory government is responsible for its own laws, policies and practices for dealing with young people accused of committing, or convicted of, offences.

However it is the Australian government, as a signatory to international human rights conventions that bears ultimate responsibility for fulfilling the rights of indigenous young people in all states and territories.

In Australia there are state and territory-based laws that breach international human rights obligations. The Australian government should invalidate these laws, or work with the states and territories to have them repealed.

Amnesty's report has identified a number of human rights violations and improvements needed to address the high rate of indigenous youth in detention, including but not limited to the below:

The Convention on the Rights of the Child (CRC), which Australia has signed and ratified, is the primary source for internationally-agreed children’s rights. Under international law, children (those under 18) have all fair trial and procedural rights that apply to adults as well as additional juvenile justice protections.

The Committee on the Rights of the Child, which monitors State Parties’ implementation of CRC, noted in 2012 that Australia’s juvenile justice system “requires substantial reforms for it to conform to international standards”.

Age of criminal responsibility

Across Australia children are held criminally responsible from just 10 years of age despite the Committee on the Rights of the Child having concluded that 12 is the lowest internationally acceptable minimum age of criminal responsibility.

Detaining children with adults

At the time of ratifying CRC, Australia made a reservation to Article 37(c) which requires children to be separated from adults in prison, unless it is in the child’s best interests not to do so. This reservation has been justified to detain children with adult prisoners where separation is not “considered to be feasible having regard to the geography and demography of Australia.” The Committee on the Rights of the Child has repeatedly recommended that the reservation be withdrawn.

Detention conditions, Northern Territory

Youth detention conditions in the Northern Territory do not appear to comply with the international human rights standards. At the Alice Springs Youth Detention Centre young people are only separated from adult prisoners by a fence. Young people are taken to the visiting block at the adult prison to speak with visitors and are handcuffed on their way to and from the visiting block.

All of the young people in detention in Darwin were transferred to a dilapidated former adult facility at Berrimah in December 2014. The previous government had planned to demolish this facility because it was old, in a poor state of repair and had an “inappropriate and outdated design.”

Mandatory sentencing, Western Australia

The Western Australian Criminal Code Act 1913 requires magistrates to impose mandatory minimum sentences on young offenders in a number of circumstances. This directly contravenes the Convention on the Rights of the Child (CRC), which states that detention for those under 18 must only be as a measure of last resort, and that all sentences, first and foremost, take into account the best interests of the child. The Committee on the Rights of the Child have recommended the laws be repealed. Instead the Western Australian government is in the process of extending mandatory sentencing.

Multiple breaches of CRC, Queensland

Queensland treats 17-year-olds as adults in its criminal justice system. CRC states that those under 18 must be treated as children in the eyes of the law. In 2012 the Committee on the Rights of the Child again recommended that Australia remove 17-year-olds from the adult justice system in Queensland. Ignoring this recommendation, in 2014, the Queensland government amended its Youth Justice Act 1992 (Qld) to require all 17-year-olds with six months or more left of their sentence to be transferred to adult jails. In 2014 the Queensland government introduced a further law which says that the court must disregard the principle that detention be a last resort, in direct conflict with CRC.

Need for more bail accommodation

Between June 2013 and June 2014 indigenous young people were 23 times more likely than their non-indigenous counterparts to be in unsentenced detention. International human rights standards require that detention for persons awaiting trial must be the exception rather than the rule. However indigenous young people are often held in detention on remand simply due to a lack of suitable accommodation and support to comply with bail conditions.

The UN Committee for the Elimination of Racial Discrimination has recommended that Australia “dedicate sufficient resources to address the social and economic factors underpinning indigenous contact with the criminal justice system”.

Justice reinvestment re-directs money spent on prisons to community-based initiatives which address the underlying causes of crime. Bourke, New South Wales is the first place in Australia to trial a community-led justice reinvestment approach to keep kids out of detention. Initiated and led by the Aboriginal community, the initiative is now tackling the social issues that get kids into trouble in the first place. They’re keeping kids in communities, where they belong.

Indigenous leaders and community organisations have consistently highlighted that more needs to be done to address the underlying factors that contribute to indigenous youth in detention through locally-designed early intervention, prevention and diversion programmes.

The current funding uncertainty, shortfalls and government cuts to specialised indigenous legal services mean that many indigenous young people do not always get the legal assistance they need.

The Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Legal Services (ATSILS) and Family Violence Prevention Legal Services (FVPLS) provide specialised, culturally tailored services for indigenous people, including young people. Numerous inquiries have concluded that both of these indigenous legal services are significantly underfunded.

Justice targets

In 2008, The Council of Australian governments (COAG) agreed to six ‘Closing the Gap’ targets relating to indigenous life expectancy, infant mortality, early childhood development, education and employment. Closing the Gap targets have improved data collection, coordination and tracking of efforts to address indigenous disadvantage across all states and territories. However despite much discussion, COAG has yet to adopt a justice target within the Closing the Gap strategy.

The National Congress of Australia’s First Peoples has consistently called for justice targets to be included in the Closing the Gap strategy.

The Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Social Justice Commissioner’s 2014 report also includes a recommendation that the Australian government revise its current position on targets as part of Closing the Gap, to include justice targets to reduce indigenous youth incarceration rates and create safer communities through reduced rates of experienced violence.

Better data for better solutions

There are many inconsistencies and gaps between states and territories in collecting data on contact with the youth justice system. The inadequacy of this information is one of the barriers preventing policy makers from more effectively responding to the over-representation of indigenous young people in detention.

For a full list of research, references and recommendations to the Australian government, please download A brighter tomorrow (Full report).

Indigenous kids behind bars are ‘a new lost generation’

Elders in the Kimberley region of Western Australia are in despair and say they’re losing a generation of young people to life behind bars. It’s a common story across the Kimberley, indigenous elders desperately trying to save a generation of young people from an endless spiral of crime and incarceration.

Sidney Griffith, 19, grew up walking the streets of Kununurra, in the West Kimberley region as a child. Eventually he started to drink alcohol and smoke marijuana in his early teens.

“I grew up walking the streets all night. I was 12 or 13 when I first started using drugs and alcohol and smoking cannabis. I used to hate the police and I never liked the red and blue. They’re especially cheeky to blackfellas when there are no other witnesses around.” At 16, Sidney was sent to juvenile detention in Perth, “I used to do burglaries, I use to do break and enters, armed-robberies, a lot of crazy shit. I felt like no-one cared about me.” Sidney would go on to spend the next three years in and out of lock-up. Now at 19 Sidney has just finished his last round of court ordered community service and says that he’s determined to stay on the straight and narrow for the sake of his five month old daughter. He says that what he desperately needed as a young teen was an Aboriginal diversionary programme. “If there was a programme when I got in trouble at that time, when I couldn’t find a programme at that time, I would have been really grateful and I probably wouldn’t have ended up in jail.” Sidney’s story is not an uncommon one.

Kimberley elder Ben Ward has been helping keep young people out of detention for the last three decades on the small remote community of Cockatoo Springs. Mr Ward has been offering young offenders a chance to turn their back on crime by taking them onto traditional land and teaching them about traditional culture. “I like to see people back on their country. I want young people to come out here, have a detention centre for our young boys here and for their detention and punishment to go through the lore, blackfella lore. We’re trying to get young people away from the system. Gudiya (white person) don’t know anything about our kids. They’re not teaching them what we should be teaching them. No-one can handle our kids, only us.” Despite helping more than 300 young offenders or at-risk children, Mr Ward says he still hasn’t received any funding or been consulted by the courts. Mr Ward warns that children and teenagers are becoming increasingly isolated and disconnected. “I have been looking after juveniles for so long and still never get no help. Not from anyone. I live on a pension and everyone of these people here, they are living off my pension because to me, I find it easy for a blackfella to look after someone.”

Allan Clarke, reporting From Kununurra, Western Australia on BuzzFeed, writes: In a small Aboriginal community outside of Kununurra in the Kimberley Aaron Griffiths, 32, says the relationship between police and the community has become increasingly acrimonious. “They come down like they own the joint, they think they got a uniform they can do whatever they want. I’ve seen young people get locked up when they could have got a second chance, but none of them [police] push that and I ask why?” Mr Griffiths says the community is desperate for help, “We are not bad people, we can be good, but there is no resources or help for young people. My biggest problem is we have got no programmes for young people and the police are not helping.”

Since 2009 The Yiriman Project in Fitzroy Valley has taken young offenders back to traditional lands to learn traditional stories, song and cultural knowledge. Elders say young people are increasingly disconnected from society and that cultural pride can be used as a way to improve self-worth. Kimberley Land Council Chairman Anthony Watson, one of the founding members of Yiriman, says programmes designed and run by community are vital in saving young people from a life of despair. “A lot of our youths don’t have nothing to live for, they take the easy way out and suicide and we want to give the responsibilities and opportunities, especially opportunities to know that they are wanted in the community and are valuable instead of feeling neglected. We want to show them they have a place, have a role, have a responsibility in the community.”

“Smacks of racism” – Dennis Eggington, Aboriginal Legal Service Western Australia

The Chief Executive Officer of the Aboriginal Legal Service Western Australia, Dennis Eggington, launched the Amnesty International report in Perth and hopes the Western Australia government heeds the report’s recommendations. Mr Eggingtion told BuzzFeed News the most pertinent issue to overcome is racism within the justice system. “I think what the report highlights is that it is not over-policing that is the problem, it’s discrimination that’s going on at every level of contact with the justice system that is the problem.” “It’s quite obvious non-Aboriginal people are getting cautions and getting diverted out of the system at a greater rate than our mob, but of course we are over-represented in that system and of course that just smacks of racism.”

Senior Aboriginal journalist, Amy Mcquire, notes that one in 77 Aboriginal boys is in detention in Western Australia at any given time. She quotes Bunuba leader June Oscar calling the incarceration numbers “horrifying” in the foreword of the Amnesty International report, and saying there is a perception from government and the rest of the community that the problem is “too hard to change” and that the “unconscionable reality” has become “normalised”. But Ms Oscar says there are “practical reforms” that can be undertaken to bring about positive change.

“Remand in police custody and then in detention is detrimental to the best interests of the child and more needs to be done to prevent unnecessary periods of remand in police custody for children in order to ensure that arrest and detention are measures of last resort,” the report says.

Western Australia is the only state in the country where a child is released on bail only if a responsible adult or welfare agency signs a bail undertaking. The report says there are often difficulties in finding an adult so that the lack of alternative bail accommodation contributes to the high numbers of Aboriginal kids in detention awaiting sentencing.

Aboriginal youth are being locked up on remand largely due to a lack of other accommodation. This is in contravention of Australia’s international obligations under the Convention on the Rights of the Child, which says locking up children should be a last resort, the report says.

The report states that police, who are the first to decide whether a child is granted bail, often refuse bail because of concerns over the child’s welfare if an adult can’t be found, or the Department of Child Protection and Family Support (DCP) is not available. But the Children’s Court awards bail in two out of three cases when it has been refused by police. The refusal of bail can have traumatic consequences for Aboriginal youth, particularly if they are from regional or remote Western Australia. The only remand centre in Western Australia is in Perth, so Aboriginal youth are often forced to travel long distances, where cost of travel can inhibit their relatives from visiting, the report notes.

The Amnesty report also raises concerns about the role of the DCP in refusing bail undertakings, saying that the Department would “sometimes refuse to sign a bail undertaking as the responsible person for Aboriginal youth people in their care”.

There are concerns that “children have nonetheless remained in Banksia Hill detention centre for significant periods of time before the Department signs the responsible person undertaking”. This is often due to a lack of suitable accommodation. There has been no formal agreement between the Department of Child Protection and Family Support (DCP) and the Department of Corrections despite a 2008 recommendation for the two to work together. There is also no formal arrangement between DCP and DCS for children with significant mental health issues or complex needs to be placed in bail hostels funded by corrective services.

Even when a child is placed in crisis accommodation by DCP, they receive breakfast only and are forced to find other food for the rest of the day.

“These young people have been granted bail but are not provided with a suitable place to stay while on bail remaining in detention,” the report says. The report also raises concerns about the role of Aboriginal organisations in designing and implementing diversionary programmes. Of the 12 organisations that are funded to deliver preventative strategies, only two are Aboriginal. And those services are critically underfunded.

While the Department of Corrective Services budget allotted only $7.83 million to those strategies last financial year, it allocated $46.8 million to detaining Aboriginal youth.

Pro-Aboriginal advocacy journalist, Gerry Georgators, writes that “justice reinvestment is worthwhile but it is no panacea; the only way to end inequality is with equality”. “It cannot radically reduce the horrific incarceration levels of Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait people. We must be solid-in-our-thinking that equality is the only campaign we must pursue, and that the steps to equality will be visible from almost immediately as we do the justice in upgrading the quality of life of our Homeland communities; when we give them what every other damn community and town and city on this continent enjoys. Governments have intentionally degraded hundreds of their Homeland communities - denying them even the most essential rights - clean water, electricity, shelter. Governments will not even upgrade water tanks. It is racialised because it only occurs in Aboriginal communities. Therefore it is racism. We need to focus on ... equality on the ground - the full suite of services, the full suite of rights, quality infrastructure in every Homeland town, community, outstation - equivalent to non-Aboriginal towns, communities, outstations."

Mr Georgatos notes that indigenous deaths in custody “are beginning to gradually decrease”. “In good part this is due to the unwavering campaigns by deaths in custody campaigners across the nation. It has taken decades but there is also no surety that deaths in custody will continue to decrease when the arrest and jailing rates are increasing. “The awareness raising I know for a fact has impacted some piecemeal changes which are saving lives. But deaths in custody continue. However, the highlighting of systemic failures and of unchecked rogue behaviours by police and prison officers must continue till these are sorted. The campaigning cannot end, not till unnatural deaths in custody are responded to with the duty of care everyone should be entitled to.”

The family of the 22-year-old

Yamatji woman, Ms Dhu, who needlessly died in a Western Australian regional

police watch-house in August last year, is still waiting for the state government to lock in the

date for the coronial inquest. “Family members are still waiting for

long overdue systemic changes and laws to be implemented that had they been in

place at the time of Ms Dhu’s detainment would have saved her life.

Grandmother, Carol Roe, said that the family is suffering while waiting for

promised systemic changes. We are all waiting for the

inquest, so the truth be known," said Ms Roe. "We are all waiting for

the changes that were promised to us in the name of my granddaughter that will

save the lives of our people."

The conservative government bears direct responsibility for failed 'tough on

crime' policies that continue to leave a trail of grief,

writes Amy McQuire. “One of the most common and distressing things that

all families of death in custody victims have to endure is the long wait for

answers. An unimaginable grief for people who have sometimes lived a lifetime

of grief builds as they deal with the few details pulled from news reports, as

they listen to the media statements that often absolve police or prison guards

of responsibility prematurely, regularly before any investigation has been

completed."

Anti-deaths in custody service could disappear after federal funding cut

Meanwhile the New South Wales Aboriginal Legal Services has stated that government funding has not been renewed for the 24-hour legal advice and RU OK [are you OK?] phone line which has prevented Aboriginal deaths in police cell custody since it began in NSW and the Australian Capital Territory (ACT, Canberra).

Operating since 2000, the Custody Notification Service was a response to a recommendation from the Royal Commission into Aboriginal Deaths in Custody whereby police must notify the Aboriginal Legal Service every time they detain or arrest an Aboriginal person in order for that person to receive early legal advice and a welfare check.

“Kane Ellis, Acting CEO of Aboriginal Legal Service NSW/ACT says he’s disappointed the CNS is being overlooked by government again despite the success of the programme,” Mr Georgatos writes. Amy McQuire reports that the Abbott government has been urged to rethink its decision.

The

Aboriginal Legal Service NSW/ACT is campaigning to save the vital

service after it lost funding under the Coalition’s controversial Indigenous

Advancement Strategy (IAS). It offers various suggestions for appealing to

politicians. New South Wales is the only state to have implemented a Custody

Notification Service (CNS) .

Australian Lawyers for Human Rights comment

that failure to fund the CNS not only raises issues concerning the

implementation of Royal Commission recommendations on custodial health and

safety and prison experience, it would also therefore not be consistent with

the spirit of Article 10(1) of the International

Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR) and Article 7 of the United

Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples.

The cost of funding the CNS phone line

is only $526,000 per year whilst the cost of holding a juvenile in detention

for one year is more than $240,000.

"The federal government is poised to abolish the Custody Notification

Service in New South Wales through a funding cut on July 1 – for the sake of saving A$526,000 a year,”

comments Eugene

Schofield-Georgeson, a practising lawyer and a PhD candidate at Macquarie

Law School at Macquarie University.

“For that modest amount, the service provides NSW with one of the most

effective strategies in curbing Indigenous deaths in police custody. The

service is a telephone hotline that provides Indigenous prisoners in police

custody with personal and legal advice. It also ensures that they receive

adequate health care while monitoring their treatment by police."

The NSW Council for Civil Liberties finds it “extremely

disappointing that this essential notification service for

indigenous people in custody is once again being threatened - particularly in

the context of the recent report by Amnesty International that showed Australia

incarcerates indigenous children at one of the highest rates in the developed

world”.

WGAR

Background: Justice Reinvestment, Aboriginal imprisonment and Aboriginal deaths

in custody (last

updated: 13 June 2015)

WGAR

Background: Plans to close Aboriginal homelands / remote communities in WA and

SA (and NT?) (last updated: 11 June 2015)

WGAR

Background: Intervention into Northern Territory (NT) Aboriginal communities by

the Federal government (last updated: 11 June 2015)

Read the Amnesty International reports

"There is always a brighter future": Western Australia full report

"There is always a brighter future": Western Australia summary report

A brighter tomorrow: National report on indigenous youth justice

Australia must back indigenous solutions to end kids' incarceration

Australia must back indigenous solutions to end kids' incarceration

See more at:

Western Australian rates of Aboriginal youth detention could breach international obligations

A brighter tomorrow: Keeping kids in the community and out of detention

ABC: indigenous youths 24 times more likely to be in detention

SBS: A generation lost if indigenous youth incarceration rate continues

Australia must back indigenous expertise to end crisis of children’s incarceration

SBS: indigenous youth 52 times more likely to end up in jail, report finds

New 'we love you' facebook site