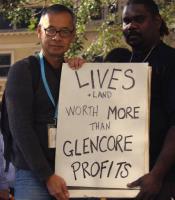

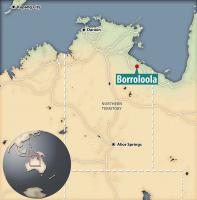

A handful of multi-generational Aboriginal people from their remote Borroloola community in Australia’s Northern Territory were front and centre at a protest outside global mining giant Glencore's Sydney headquarters on May 19. Glencore’s McArthur River mine, the world’s largest open cut lead and zinc mine, has polluted the river, which has been a major source of food and is sacred to them. Members of the Borroloola community, located 954 km (10 hours driving) south-east of Darwin had travelled hundreds of kilometres for two days by bus and plane to stand in front of Glencore’s Australian headquarters in Macquarie Place, central Sydney, and call for justice.

The protest was organised by green groups, including the Mineral Policy Institute and ActionAid Australia. MPI's Lauren Mellor said: "The response we've had back from Glencore is to agree to a meeting with the Borroloola community, where the community will present its management strategy and proposal for the closure and rehabilitation of the mine site."

Instead of waiting to see what Glencore proposes, Borroloola residents have commissioned an alternative plan to close the mine. Activist Mellor has facilitated it and says residents are worried Glencore's mine will be left leaking into the environment like many other old mines in the area.

“They want to see a fully costed and comprehensive closure plan and so they've actually fundraised, through the sale of artworks, to raise their own funds to bring on a team of experts who are recognised around Australia as being experts in lead pollution and legacy mine containment and acid metalliferous drainage.”

“We were privileged to get behind the traditional owners of the Borroloola indigenous clan groups to demand that greedy multinational miners Glencore shut down their mine on in the Northern Territory,” wrote the global action!aid group, which ran similar protests in other countries on on the day Glencore held its corporate annual general meeting in Switzerland.

Long opposed by local indigenous clan groups, the McArthur River mine has for over a decade breached mining laws, creating an environmental crisis in an area famed for its excellent fishing.

The Sydney protest was also about Glencore’s tax evasion. Also Australia's largest coalminer, Glencore, paid almost zero Australian tax over the past three years, despite revenue of $15 billion.

“The action was a huge success,” action!aid wrote. “And all around the world, from Peru and England to South Africa and Bangladesh, people joined in calling on Glencore to clean up their act and #makethempay their taxes.

“Greedy multinationals move into low-income communities, pillage land and resources and then – on top of that – they avoid paying their fair share of taxes – taxes that are essential for funding basic public services that protect the rights of women and their communities,” the group writes on its website.

"Stop polluting our river. We want you to clean the river before you leave. This is your mess [Glencore]. You dig. You clean it up,” said Borroloola resident Nancy Yukuwal McDinny (see video below),

one of several passionate speakers at the rally of a few dozen people. They called for immediate closure of the McArthur River mine and for Aboriginal clans to be compensated over the damage caused to the land.

McDinny, told protesters: “I grew up in that river and now I cannot see any food in the river that we used to eat (video). They are all gone, dying from the McArthur River mine.

“Instead of keeping the pollution in the mine area they are putting it down to the river, where we used to get our bush tucker, and it is going out to the sea. A long time ago, when I was still going to school, our old people fought this mine. I heard them fighting so hard. Now it is our children who we are fighting for. We need that McArthur River mine to be closed.”

“It’s important that we stand in solidarity with communities like Borroloola, because at ActionAid, we see this story unfold in countries all around the world in which we work.”

Concerns about the mine were heightened after reactive rock in its waste dump began spontaneously combusting in 2013. The huge man-made mountain of burning waste rock spewed toxic sulphuric fumes into the sky. The smell was grossly rank so windows had to be closed. The company extinguished the fire last year but residents are still worried that the reactive waste rock is polluting the McArthur River system.

Revelations that fish in tributaries of the McArthur River have been contaminated with lead for several years have alarmed the Aboriginal traditional owners.

The Australian Broadcasting Corporation, the multilingual Special Broadcasting Service and The Guardian’s web platform were among a host of media covering the action in Sydney.

The immense McArthur River flows to the sea through what Australians call the “Gulf Country” and in addition to the Gudanji around Borroloola, its poisoning also affects the Garrwa, Yanyuwa and Mara clans. Borroloola sits on both banks, like two separate towns, about 50 kilometres from the estuary.

When the Glencore mine’s giant toxic waste dump spontaneously ignited, serious questions were asked about how it could have happened and why regulators allowed a mine to operate with no known solutions to its massive waste problem.

Documents show that the Northern Territory Mines Department dismissed Glencore's assurances over security bond and fish, as the mining giant attempted to downplay the seriousness of the McArthur River contamination and tried to argue against having to increase its environmental security bond.

Clan groups in Borroloola and the South West Gulf of Carpenteria are also working together to protect country from fracking. In October 2014 Borroloola Elders led a march across the McArthur River Bridge as part of the Global Frackdown, an international day of action against fracking.

After the protest in Sydney, Nancy McDinny was interviewed about fracking on Aboriginal radio in Alice Springs.

Three young leaders from the region have explained how Borroloola and surrounding homeland communities have fought for generations against destruction of their lands by mining and how youth are stepping up the fight for climate justice (interview).

“We are carrying on the fight of our three great-grandfathers. We looked up to them, they passed their knowledge of the country down to us. The songlines, how to live in the bush, how to hunt. Which places to go and which places not to go. They have been looking after the country for a long time. It’s our sacred duty to keep up that legacy.

“We have stories, songs and dances that connects us through the land that we live on. That’s what drives us to fight. It was put in to my Nanna’s heart and Grandfather’s heart by their Grandparents. Now it’s on to us. It’s our responsibility."

Previous linksunten

report on this issue

Tourism promotion of the Borroloola area

Video of female Elder, Aunty Nancy Yukuwal McDinny: “We can’t eat food from the river anymore”

Video with clapstick singing and speeches

Video: “This is your mess, you clean it up”

Borroloola clans gain more native title rights over NT cattle stations

Other recent Aboriginal news on linksunten

Elation, sadness and anger over return of north Australian Aboriginal land

“Don’t let Australia into the United Nations Human Rights Council”

Help Aborigines close a community-destroying mine

“Language, culture, ceremony needed to fight Aboriginal suicide”

$150 million for reform of remote Aboriginal communities not spent

After 26 years no justice for Aboriginal families whose three children were murdered

Further evidence that the Commonwealth of Australia does not have a legal sovereignty

Aboriginal owners outraged by a spiritually important site being chosen for Australia's first nuclear waste dump

Another month’s walk with Aborigines against uranium mining

12th police raid on Aboriginal protest and homeless camp

Why no-one should climb Uluru

Found her Aboriginal identity

Jade Jones-Cubillo writing at IndigenousX

‘I had always thought to be Aboriginal you had to look it. I thought you had to inherit certain features for others to recognise your background. Wrong.’

Here I am at 20 years old sitting in the backyard on a chair I’ve sat on many times before and contemplated many things throughout my life and find that I have continuously asked myself: “What does it mean to be Aboriginal?”

I’ve grown up in a western setting, right in the heart of Darwin. When I explain my mob I say it’s like saltwater meeting freshwater, I walk in the best of two tribes.

I am a Larrakia and a Jawoyn woman that I inherited from my father, grandfather, grandmother and my ancestors. I am also English, my grandmother on my mother’s side comes from the United Kingdom.

I have experienced the culture, the lifestyle and the white history of Australia my whole life but my cultural knowledge about my Aboriginal heritage is limited.

While I had been taught who my mob was, I didn’t understand how special and empowering it was to be of Aboriginal heritage till I was 17. I had been chosen to go to an Indigenous Leadership Academy in Sydney and I thought, “If I am going to prove to these mob I am Aboriginal, I better learn everything there is because I don’t technically look it”. I immersed myself in any cultural opportunity that came by and in doing so, unlocked many questions as well as my curiosity.

Throughout my schooling life, I had not learned about the black history of Australia. I had briefly touched on the stolen generations because my class had to analyse the movie Rabbit Proof Fence but I never learned the reasoning of why it had happened. I never learned the effects this had on the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander mob of Australia.

Instead, I learned the history of other places. I spent a term learning about the Holocaust. I learned about the second world war. I learned the reasoning behind such a horrific event. I was taught about the trauma, the effects that it had on those people and how upsetting it still is for people of that heritage to speak of what happened in that era.

I taught myself about Australia’s black history, at 17. I was curious and didn’t understand why this wasn’t something we learned at school. I learned that the stolen generations and many other events had heavy-hearted effects on my people. I started to understand why we have such loss of culture, why some of my Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander friends didn’t know where their mob was from and why this is such a hard thing for my mob to talk about.

And I felt sad that my mob still suffer from the trauma of those days. I felt sad that my own grandmother, who is still with me today, had been part of one of Australia’s darkest events regarding the First Nations people.

I started to feel and I started to want.

I wanted to know more about my people and I wanted to know more about myself and what it means to be Aboriginal. I wanted to find my identity.

I had always thought to be Aboriginal you had to look it. I thought you had to inherit certain features for others to recognise your background. Wrong.

I remember talking to my boss who is a proud Gabi Gabi man and another colleague of mine, who is a mixture of Aboriginal cultures from Melbourne. We were in mid-conversation and I said to my boss in a joking tone, not even thinking it was the wrong thing to say, “You wouldn’t even know you were Aboriginal, you don’t look it.”

My boss, a proud Gabi Gabi man, is tall with orange hair, blue eyes and freckled skin. Who was I, another Aboriginal, to say “you don’t look the part”? My colleague, who had previously been my mentor, said: “There is no certain way to look, if you are Aboriginal, you are Aboriginal.”

It’s almost been a year since that moment.

Since 17 years of age, my perspective on my Aboriginal heritage has changed rapidly and my knowledge of my heritage has grown into pride and a journey to find my own identity.

Bowraville families cautious as child murders to be retried

After years of disappointment, the families of three Aboriginal children murdered 25 years ago have welcomed a surprise development that could see justice finally done.

The alleged serial killer is a step closer to being tried for the murders in Bowraville on the New South Wales mid north coast, after the Attorney-General bowed to public pressure and announced the highest criminal court in the state would be asked to hear the case.

A family member of one of the murdered children and a Detective Inspector who's been fighting for justice alongside the families have responded to the development on a major TV current affairs programme.

NSW upper house Greens MP David Shoebridge led the push laws to be changed to make the new trial possible. “Those families have finally got a fair shot at justice, they're going to have their day in court," he said.

Remote mental health training needed for Aborigines

“Young Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people take their own lives at a rate five times that of other Australians ,” “This is devastating Aboriginal communities and we must do everything in our power to try to save these young lives.

“If we can train up young people and others in our communities to recognise and react to the warning signs in their peers, there is a good chance we can support those who are suffering before they reach the point of no return.

“This is a good initiative which empowers communities to be part of the solution."

Matthew Cooke NACCHO Chair