How do the police function? Where are its weaknesses, and how can we circulate a knowledge of them? Where do they resupply themselves? How do they move? Who arms them, and how? These are the sorts of questions that we must ask ourselves in order to envision new ways of acting. We must know their weaknesses if we are to be able—at the opportune moment—to be able to reduce their industry’s capacity for disruption.

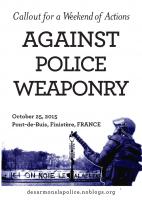

On October 25, 2015 we are organizing a weekend of actions against the Nobelsport factory, producer of tear gas grenades and flashballs. The aim is simple:

- To achieve a breakthrough in imagination, by seeking-out new sites of police vulnerability, and by making visible the origins of the weapons that mutilate and kill our comrades in France and abroad.

- To collectively develop the techniques needed to block such forms of industry.

Background

After ten years of repeated assassinations and mutilations, 2015 marked a major turning point for the degraded image of the French forces of order.

During the 2000’s, French streets were filled with the rage of the banlieus, followed by thundering student upheavals. Both brought to light a principal trait of policing [le maintien de l’ordre]: namely, that its essential nature is that of a dissuasive force designed, where need be, to contain confrontation by means of premeditated apparatuses.

More recently, in the countryside, the forces of resistance against large infrastructural development seem to have triumphed momentarily over French savoir faire in matters of territorial control. Having literally bogged themselves down in Notre-Dame-des-Landes, the gendarmes followed up this shipwreck with a predictably frantic deployment of weapons at the Zad du Testet on the 25th of October, 2014, leaving countless wounded, and killing 21-year-old Rémi Fraisse.

Then there’s all the self-fashioned experts of internal security, who committed one of the bigger failures of their newly-launched career in 2008 with the whole “Tarnac affair”. In a matter of weeks, the figure of the internal enemy they had only just cobbled together ended up digging the grave of the very people who sought to wave it around as a boogeyman. Exeunt MAM, Judge Fragnoli, the spooks of the DCRI, who suddenly all slipped out the back door.[5]

And if we had for a moment lost the taste for those little dirty wars carried out under the purview of the internal security services, the Tarnac affair has brought it back afresh. As did the story of the Basque militant Jon Anza who disappeared in 2009 while aboard a train to Toulouse, only to anonymously reappear a year later, in a morgue.

It was against this backdrop that the unexpected attack against Charlie Hebdo took place in the first days of 2015, in the course of which several police died. The drums of international war were hastily sounded, with everything done to orchestrate one of the most spectacular mobilizations in recent years. With the people suddenly standing tall behind the police, the lengthy balance sheet they accumulated over more than a decade was swiftly wiped clean. Tens of thousands of people marched alongside heads of state, cheering at the snipers guarding the demonstration: a beautiful demonstration of the force of antiterrorism, which had finally found a popular translation. And over the two months that followed this morbid event, the state methodically answered to each of the errors it had accumulated:

- 6th of March: the Zad du testet in Sivens was evicted by 200 farmers from the FNSEA[6], accompanied by a heavy contingent of gendarmes who assumed the dubious air of neutrality so as to avoid escalating the violence.

- May of 2015: the high court in Paris rejected the civil suit lodged by Jon Anza’s family. Despite acknowledging “dysfunction within the investigation on the part of both the police and the prosecutor”, it claimed that there were “no major mistakes”.

- 18th of May: after a ten-year investigation, the

two cops responsible for the death of Zyed and Bouna in Clichy-sous-bois in

2005 were let off.

- 7th of May: the press announced the continuation of the anti-terrorism trial for three people accused in the Tarnac affair.

Around the same time, the parliamentary commission put together by Noël Mamère following the death of Rémi Fraisse began equivocating about the means employed by the police, while simultaneously approving new armaments for them. The immediate outcome was an upgrade of their flashball weaponry with more accurate and powerful models.

And, to top all of this off, a new law has now been proposed seeking to legalize all the surveillance techniques that the police were already practicing in an unofficial way.

The message has at least the virtue of being clear: nothing will stand in the way of the maintenance of order which, with its freshly renovated imaginary, now confers on each of its agents the most respectable task of protecting the population against organized chaos. What it forgets to mention is that from the point of view of power, the organized chaos that must be conjured away has little to do with the specter reinvented by Bin Laden, but resides instead in all the modes of living, inhabiting, encountering one another, and self-organizing that escape the analytical frame of the present.

Nevertheless, it is not a secret for anyone today that the police kill, that they kill every year, again and again, with the same weapons and under the same authority, and that when they don’t kill they mutilate. And while this truth has long-since been a painful banality for those inside of the French banlieues, it has been remained inexistent in demonstrations.

Since the death of Malik Oussekine in 1986, policing à la française has served as a model for the rest of Europe. An undeniable know-how, coupled with reliable—albeit increasingly deadly—weaponry. For over ten years, and across diverse terrains of struggle, their proudly publicized mastery has tested itself against new levels of determination and a widening field of confrontation: arsons and lootings in the banlieus, confrontations in the countryside, the generalization of blockade tactics around the CGT, sabotage of machines and high-tension lines—the authorities have not lacked in opportunities to measure their forces against ever more heterogeneous forms of contestation. For ten years the police have ceaselessly adjusted their methods of intervention, with each new conflict, each new setback serving as a chance to improve their capacity for intervention, to refine their doctrine.

A recent article states that in France the use of offensive grenades is permitted only within three sorts of territories: banlieus, overseas departments and territories, and within the ZADs. It would seem that what the ruling powers prefer to describe as lawless zones [zones de non-droit] now enjoy a particular status, which has the effect of transforming them into little laboratories for state authorities.

After the banlieues, the factories, the universities, the high schools, today it is the ZADs and their urban counterparts that serve as the principal objects of study for the entrepreneurs of security.

Overcoming Fear

A certain anxiety is unmistakable within movements of struggle concerning the destructive effects of the weapons that police wield against us in a virtually systematic way these days. Whereas we were surprised to note how few people took to the streets after Rémi’s death, it was rather unsurprising to witness the sorts of cleavages this sequence reintroduced in our movements. Although to some extent justified, a fear of watching a repeat-display of the same apparatus of confrontation producing the same consequences seemed to hold sway over the massive reaction to this assassination, wavering between a feeling of weariness in the streets, and a feeling of deprivation for those who feared the confrontation, feared being wounded, etc. For their part, the police responded by simply cutting off the entire downtown areas of cities, and spreading fear through repeated media assaults.

Nevertheless, something tellingly important took place. Although a certain fear enveloped the atmosphere of the autumn demonstrations like a thick cloud, with every demo (as in Toulouse and Nantes) more and more people kept showing up. In the end, it was above all time and repetition that worked against the demonstrators more than anything. Still, whether by taking the street, or by blocking the gendarmerie or weapons factories, we saw these days as the sign of a kind of bottled-up anger in search of an appropriate form of expression.

Fear is a paradoxical emotion, tending sometimes towards withdrawal, other times towards its own overcoming. The first reaction (the most pronounced one) kills movements, or else maintains them in a state of prolonged agony. Everyone is terrified of taking the next step, whether it be of advancing more confrontational tactics, or having to watch one’s comrades dissociate themselves from certain kinds of acts, or betraying one’s own political identity, etc.

All of these fears are at once the consequence and the motor of repression, which aims to exploit breaches in the fragile state of our composition in order to diminish the power of movements.

The best defense against such an effect is to seek out the conditions for the construction of a form of collective confidence, not so as to suppress disagreements, but rather to enact certain strategic necessities within struggles that confront the state apparatus. It was this sort of confidence that allowed us to rebuff two thousand cops on the ZAD in 2012, to block a train loaded with nuclear waste for several hours in 2011, to draw five hundred tractors into the streets of Nantes, and to disrupt the raids against the sans papiers in Montreuil.

There is no hidden destiny lurking behind the obstacles that our experiences run up against, only overcomings that remain possible.

Shifting the Conflict

There is no doubt that the question of conflict is one of the perennial knots in the struggles we lead together. Some situate its proper terrain on a juridical level, others within the media and public opinion, while others see it as having its place in street confrontations. There is no shortage of splits on this account.

At the same time, a lot of us would likely agree that it is in fact a certain combination of all of these that makes us strong, that gives us the capacity to dismantle the most audacious incursions of the forces of order.

Combining these different forms removes each of them from its isolation:

To reduce the political confrontation to the fight in the streets is at best to tell oneself one has frightened the powers that be, and at worst to lose an eye or one’s life.

The bottomless faith in “public opinion” only ends up handing over our capacity for self-enunciation to journalists, who consequently enjoy a monopoly over political thinking.

Finally, to hand oneself over to justice testifies to a blind faith in an supposed independence of the courts that was in fact extinguished during first minutes of their creation.

However, combining these three dimensions provides each one of them with the means to withstand the relations of force they run up against—and to do so precisely by displacing the terms of the conflict.

The strength [puissance] of the forces that maintain order can remain active only so long as it confronts an opponent that has submitted to the symmetry they impose upon him (or that they are able to supervise, as was recently the case with the ZAD du Testet).

Shifting the conflict does not imply a renunciation of the practices of struggle that brought our force into being. Rather, it is a question of stripping them of the isolation imposed upon them by the authorities: to sidestep an apparatus rather than confronting it directly; to use the law to highlight the irregularities in police operations, and thereby to slow them down; to foil in unison the artificial figures the media constructs of us—in short, to afford ourselves every strategic means and possibility rather than clinging to immutable truths.

The French arms industry has the double particularity of being at the helm of the international project of maintaining order, while enjoying a relative invisibility as regards the destination of its products. If the Greeks who suffer the police on a daily basis have a hard time attacking those who produce their weapons, it’s because the weapons that mutilate them come from France. Similarly, the teenager who met his end during the anniversary of the occupation of Gezi Park in Turkey a year ago was killed by a French grenade. It is the same with the Arab insurrections. Everywhere the French arms industry produces the same disaster. To make such an industry visible is also to remove it from the niche in which it remains concealed, and to begin seeking out the necessary means to block it.

Practices of Struggle

How do the police function? Where are its weaknesses, and how can we circulate a knowledge of them? Where do they resupply themselves? How do they move? Who arms them, and how? These are the sorts of questions that we must ask ourselves in order to envision new ways of acting. We must know their weaknesses if we are to be able—at the opportune moment—to be able to reduce their industry’s capacity for disruption.

The idea of gathering at Pont de Buis has its origins in the demonstrations last December following Rémi Fraisse’s death. At that time, two hundred of us found ourselves in front of the Nobelsport gates without really understanding the exact nature of what lay behind them. However, this experience taught us something, which is that in order to halt their production, it suffices to gather only this many people in front of their gates. Sites that produce explosives have extremely strict regulations, which place limits upon them. It turns out that simply being a hostile presence is enough to interrupt their production. Presently, we wish to go further in our experiments with tactics for blocking such an industry. How do the production units function? What roads do their transports follow? Where do they stock such goods? In short, we aim to drag into the light the secret little economy that constitutes police armament, and thereby to develop the means to disrupt it.

Why Nobelsport?

Nobelsport is among the largest production sites for police weapons in France. It took over the Pont de Buis gunpowder factory in 1996, and on this site continues to produce grenades, cartridges, etc. It supplies the police as well as the army, while also marketing its products to numerous foreign countries. There are four facilities dispersed across France, with a headquarters in Paris. The company is run by a group of seven majority stockholders drawn from the arms as well as the finance industry. In short, it is one site among others, and we would find it no less useful to target Alsetex (in Sarthe) or Verney Carron (in Sainte Etienne), or any other business supplying the forces of order, from the uniforms on their backs to the paint on their vehicles.

The Nobelsport factory covers roughly half the space of the town, surrounded by several kilometers of wire fencing. The arms industry has a long history in the surrounding region: from the Chateaulin gendarmerie training site to the nuclear submarine base, institutional authorities have long been heavily present in the area. Aside from its historical role in the military adventures of Louis IV, what we associate most with this factory are the sad realities that come with highly explosive industries, realities that have carried away the lives of numerous workers along with the windows of local houses. The period between 1975 and now offers several chilling examples for anyone who wishes to imagine what it’s like to live next to a gunpowder factory.

A Brief Note to Our Friends From Elsewhere In Europe :

We think it is very important that many people from all around Europe participate in this weekend against police weapons. After all, these weapons are exported internationally. The bullets produced in this factory are deployed against social movements all over the world. We see the global spread of such a strategy of attacking police infrastructure as a means of transcending the limits of classical anti-repression strategy.

This weekend will serve as an occasion to link the local mobilization against this factory, which is still in its early phases, to the global situation. We ask that people who come try to be attentive to the local situation, to the links that we are slowly constructing with locals living in the vicinity of the factory. For us, this weekend is only one step in a long-term strategy of organizing together with these locals, who already blocked the factory once during the eviction of the ZAD, and could do it again in the context of other social movements. Actions carried out here should therefore ideally be coordinated with us (the organizing collective) and should aim to contribute to the local strategy. There will be offensive gestures elaborated, but they will be those that we succeed in thinking-through collectively with the folks from the area. Thanks in advance! And see you soon!

ALL OUT TO PONT-DE-BUIS!

The Pont-de-Buis Collective, 2015

For more information and updates: desarmonslapolice.noblogs.org

PRINTABLE ZINE OF THIS TEXT: http://ill-will-editions.tumblr.com/post/131258686334/callout-for-a-weekend-of-actions-against-police

Judge Thierry Fragnoli’s lack of impartiality forced him to recuse himself from the Tarnac case in 2012 following an article published in Le Canard enchaîné.

The General Directorate for Internal Security (Direction générale de la sécurité intérieure), an intelligence agency created in 2008, through the merging of the direction centrale des Renseignements généraux (RG) and the direction de la surveillance du territoire (DST) of the French National Police. It reports directly to the Ministry of the Interior.

For a detailed interpretation of the Tarnac Affair written by the accused, see Bye-Bye St. Eloi! Observations Concerning the Definitive Indictment Issued by the Public Prosecutor of the Republic in the So-called Tarnac Affair. In English here: http://www.notbored.org/bye-bye.pdf

Fédération Nationale des Syndicats d'Exploitants d'Agricoles, a conservative umbrella organization gathering thousands of local agricultural unions.

A French-Algerian student who died in police custody after being arrested during student protests against university reforms and immigration restrictions.