On April 16, a small group of protesters excitedly marched into Tahrir Square, only to be chased out again by police forces with tear gas minutes later. “Revolutionaries are in Tahrir Square,” activist Alaa Abd El Fattah tweeted. “It’s true that we ran in and ran out but we will still consider it an achievement." Following this protest in Tahrir, which has gone from the hub of the revolution to a restricted area for protests, the movement made its next large march to the presidential palace in late April.

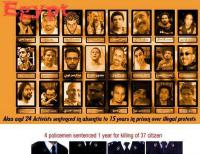

Today, Abd El Fattah was arrested from outside a courtroom where a judge had just sentenced him to 15 years in absentia for illegally protesting and assaulting policemen, among other charges.

His arrest, alongside Wael Metwally and Mohamed Noubi, has caused an uproar among activists, whose space has been dwindling. Their fight now is about holding ground.

Zizo Abdou, member of the April 6 Youth Movement, which was recently banned, says he and other activists are cautiously but defiantly trying to reclaim “the lost territories of the revolution.”

Three years down the road of an anti-regime mobilization that brought millions to the street, being able to merely hit that same street in an act of protest today is held as an achievement by this meager group that wants to keep going.

Nowadays, this group chooses audacious locations and escalating measures, and attempts to avoid confrontations with the police, which have proved costly in recent months. A protest often ends shortly after people arrive and other protective measures are taken such as inviting public figures to participate.

They argue that the day the revolution ceases to be seen in the streets, albeit in a weakened condition, will be the end.

Abdou is one of a few activists who initiated a campaign in April demanding the annulment of the Protest Law, issued last November, which imposed strict limitations on the right to demonstrate and freedom of assembly.

He says the concrete victories of the campaign have been limited. In some cases it was able to improve the prison conditions of detainees or draw attention to certain cases.

But the campaign has another main function.

“The success is the idea of continuity, in this difficult state and great danger, to keep going and say 'no' is a win. If I shut up and stay home it would be a huge victory for the state, and it would succeed in — not weakening — but eradicating the revolution altogether,” he says.

For Abdou, the revolutionary movement is hanging on by a thread to the tiny space that remains after the state’s crackdown on the political space in the wake of the ouster of Mohamed Morsi and the Muslim Brotherhood last year. Ever since, this revolutionary movement that has survived the reduction of national politics to state-versus-Brotherhood, has been trying to expand this space, figuratively and literally.

Activist Khaled Abdel Hameed, says that the mere presence of a street movement unsettles the intended scenario of the current regime, recently crowned by the inauguration of former military commander Abdel Fattah al-Sisi to the presidency. Similarly it unsettles the Muslim Brotherhood's tendency to hegemonize politics.

“Both parties of the battle are keen on suggesting they are the only players on the scene. Our presence challenges that,” he says.

State crackdown aside, the Brotherhood has criticized this group of mostly secular activists, accusing it of not taking a strong enough stand against the crackdown on its own members. The campaign of anti-Protest Law activists has made a point of focusing on all political detainees regardless of their political affiliation. However, on many occasions Muslim Brotherhood detainees refused to use lawyers sent by the campaign to attend interrogations with them.

Abdel Hameed adds that in the absence of independent protesters in the streets the state could succeed in propagating deposed President Hosni Mubarak's myth that the Muslim Brotherhood is the only opposition to the government, and easily eradicate all opposition.

“It is important to carve a third way, difficult as it is,” he maintains.

Many activists say the current period is the worst in the short life of the January 25 revolution and the most difficult in their personal history of activism.

While he remains hopeful, believing that the strongest movements are born in the hardest situations, Abdou says that the current situation has unique challenges that are different from the political drought that he witnessed under Mubarak.

In the last few months, the revolutionary camp, namely those activists that refuse both the militarization and the Islamization of politics, has shrunk, while entering into its most difficult battle yet. Many of the groups, parties and figures considered to be “revolutionary” have changed camps and are now on the state’s side. Others remain in the opposition but have stayed away from the street, deeming it too dangerous.

Those who are still active have become state targets, beyond the crackdown on the Brotherhood.

“The state is personalizing its battle with the youth of the revolution, and insists on picturing them as the cause of all chaos,” says Abdou. Both prominent and lesser known activists have gone to prison on protest charges.

Lack of popular solidarity with the political crackdown is another challenge.

“Before the revolution there was hidden popular support. When people would see us in a protest they would be with us but too afraid to join. Now the people harbor a hidden support for the state that’s killing us,” Abdou says.

The turnout at protests is incomparable to the numbers that were in the streets in recent years. When Nourhan Hefzy, the wife of prominent activist Ahmad Douma who is sentenced to three years in prison under the Protest Law, called for a women's sit-in at the Ettehadiya Presidential Palace in April to demand the release of all detainees, less than 10 women showed up. The women spent the night with a number of officers that outnumbered them close-by, expecting to be attacked at any second.

Abd El Fattah, who spoke to Mada Masr days before he returned behind bars, says that the constant state of emergency that the revolutionary movement has been going through during the last three years has taken its toll.

Amidst working on the cases of other prisoners of conscience, Abd El Fattah has constantly anticipated his own arrest.

“We have been busy putting out fires. We didn’t have time to take a breather or think about anything other than the right to live and the safety of the body, which is a good thing if we embrace it,” he says.

For him, once the intensity of the crackdown breaks, activist groups should work on not merely holding revolutionary ground, but preparing it, strengthening its own organization and attracting more people. Abdel Hameed shares his view, saying that the movement’s main function is to remain ready for the people’s next uprising.

But for Abdel Hameed, it is socio-economic demands, spearheaded by the labor movement, that will make people rise against the current regime. These are bound to happen, he says, in light of the government failure to bring concrete gains to ordinary Egyptians. While the people are currently making excuses for the state’s violations of rights with elaborate conspiracy theories, he says that when the government fails to respond to social demands, there won’t be as much space to maneuver.

“The political forces have to be able to build a bridge between political and social battles, we didn’t succeed in that last time,” he says.

Loss of hope is held as the one burdensome challenge.

Throughout the last three years, the revolution that ignited an explosion of hope and aspirations for long-time activists as well as ordinary Egyptians has seen more defeats than victories.

“It’s a tough situation, we struggle out of necessity, despair is not an option and hope is a luxury,” Abd El Fattah says, admitting that he personally is in a state of despair and defeat, but believing that a continued struggle has become a matter of life and death for his generation and that of his son.

However, Abd El Fattah says that while activists believe in the importance of the struggle, even when they temporarily lose sight, the crowds will not follow them until they see that hope.

Abd El Fattah says that the common perception that fear is what stopped people from acting under Mubarak is false. "It was the lack of hope," he says. While this hope was induced by seeing Tunisia triumph in 2011, this time around activists have a mission to somehow “manufacture hope” again and make people believe once more that change is possible and that their sacrifices won’t be in vain.

Anmerkung rg: Dieser Text wurde gestern (12.06.2014) auf Mada Masr veröffentlicht, nachdem

Abd El Fattah und 24 weitere Angeklagte zu 15 Jahren Knast verurteilt wurden.

Siehe auch: